What Were the Orphan Trains?

The real-life history behind Wanderville.

The orphan trains were a series of social service programs that relocated poor and homeless city children.From 1854 to 1929, more than 200,000 children traveled by train from the East Coast to seek new homes in nearly every state in the continental United States.

Poverty in the Cities

By the mid-1800s, millions of people lived in poverty in East Coast cities like Boston and New York. Many were immigrants who had recently arrived from other countries seeking a better life. Others had come from more rural parts of the U.S. to work in factories. As a result, cities were growing, and some areas, especially poor neighborhoods, were becoming extremely crowded.

In one such area, New York’s Lower East Side, people lived in tenements, densely populated apartment buildings that were run-down and unsanitary. Many families lived in just one or two small, cramped rooms which often lacked direct sunlight or even windows. Some tenement apartments housed illegal factories, where workers sewed garments or assembled items like brooms or cigars, working long hours for low wages. Children were among the urban poor. They lived in slums and tenements with their families and many worked in factories—sometimes instead of going to school.

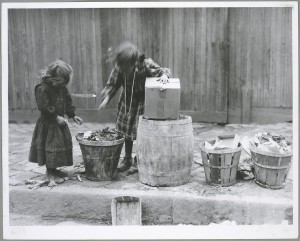

A great many children were homeless as well. The polluted water and filthy living conditions in big cities led to epidemics and other diseases that left children orphaned. Some children were abandoned by parents who were too destitute to raise them; others were runaways escaping abuse or neglect. Although many private charitable and religious organizations operated orphan asylums, they were often filled to capacity. Thousands of children lived on the streets: they begged strangers for money, foraged through garbage, and slept in doorways and alleys. Some even turned to crime, picking pockets, stealing food, or joining street gangs. All of these children were commonly known as “urchins,” “waifs,” or “little wanderers.”

The Children’s Aid Society

In the 1850s, a minster named Charles Loring Brace went to work in New York City as a missionary dedicated to helping the poor. When he saw how many children were homeless, he founded an organization called The Children’s Aid Society. Brace felt that orphanages weren’t the best solution for these children. He also believed that if they grew up on the streets, they would become criminals as adults. Through the Children’s Aid Society, his goal was to send these children far from the cities to live in the country, where he thought they would have better lives.

At first the Children’s Aid Society placed children in rural households in New England and upstate New York. But advances in railroad travel made it possible to send larger numbers of children farther west. In 1854, the Children’s Aid Society sent its first group of 46 children by boat and train to Dowagiac, Michigan. When the children arrived there, the town residents and local farmers were invited to choose a boy or a girl to take home. The trip was considered a success, and over the next sixty years, many more trainloads followed, carrying children to the Midwest and beyond. Other charity organizations began to send children on trains as well, from Boston, Baltimore and other East Coast cities in addition to New York.

Being “Placed Out”

Many of the children who rode the orphan trains came from city orphanages. But a significant number of the train riders were not full orphans at all—they had at least one living parent who had given them up in order to save them from a life of poverty. Once they boarded the trains, most children never saw or heard from their birth families again. They were given new clothes and sometimes a Bible, and they traveled in groups escorted by at least one adult. The train journeys would often take several days.

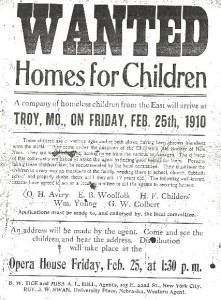

The trains stopped at towns where people were waiting to see and select the children. A train’s arrival would be advertised in advance, with handbills, posters, and notices in the newspapers. Some people were interested in choosing a child to raise as their own. Others, though, were looking for older children who could do housework, farm chores or other labor.

At each stop, the orphan train riders were lined up at the train depot or other public area while people looked them over. Boys and girls were often inspected closely to see if they were healthy and suited for hard work—people looked into their mouths to check their teeth or felt their limbs, treating them much like livestock. Sometimes a child would sing a song or recite a poem in order to make a good impression. Unless they were lucky enough to be chosen by the same family, siblings were often separated and sent to live in different homes from one another. Once the selection process had finished, any children who were not chosen would return to the train with their escorts and continue to the next stop, where the selection would begin again.

Many children were adopted into the families that chose them. Some, however, were little more than servants, and some were abused, neglected, or overworked. While the Children’s Aid Society tried to check on the children they placed and make sure they were treated well, it was often very difficult to follow up. Sometimes, when there were problems, a child would be sent to a new home. Other times a child might simply run away.

Despite these problems, the orphan train program made a difference in the lives of many children. A number of them went on to be successful in adulthood. Two members of congress and a Supreme Court justice rode the orphan trains as children, and two boys who were on the same train in 1859 became the governor of North Dakota and the governor of Alaska.

The orphan trains stopped running in 1929. By then, the ways to help homeless children were beginning to change. More government social programs were established to help the poor, and large orphanages were being replaced by foster homes. Many years after the last orphan train ran, a museum in Concordia, Kansas was built to remember the thousands of young riders.